Essays from Joan Didion, George Saunders on why fiction matters and plenty more.

If your days are feeling monotonous, you might find entertainment and variety in this flurry of new books about subjects that span the globe. A Danish writer’s collected memoirs trace her effort to nurture artistic ambition in spite of a grim family life and, later, addiction. A biography revisits the lives of two pioneering sisters who paved the way for women to practice medicine in the United States. And a debut novel imagines a romance between two enslaved men in Civil War-era Mississippi. No matter what you’re seeking, you can find it in the pages of a book next month.

‘Aftershocks: A Memoir,’ by Nadia Owusu. (Simon & Schuster, Jan. 12.)

Owusu’s life has been a series of upheavals: She has lived across the world, thanks to her Ghanaian father’s work with the United Nations, and was all but abandoned by her Armenian-American mother. Eventually, settling in New York as an adult gives the author a chance to make sense of her identity. Images of earthquakes and their aftermaths recur throughout the narrative: As Owusu notes, aftershocks are the “earth’s delayed reaction to stress.”

The Copenhagen Trilogy: Childhood, Youth, Dependency,’ by Tove Ditlevsen. Translated by Tiina Nunnally and Michael Favala Goldman. (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, Jan. 26.)

Ditlevsen was well known in her native Denmark by the time she died, but few of her works have broken through in English. Her novel “The Faces,” perhaps her best-known work, details the unraveling of a children’s book author. Ditlevsen’s three memoirs, originally published in the late ’60s and 1971, are collected here in one volume. She writes about growing up in working-class Denmark on the precipice of World War II, nurturing her creative ambition and navigating her relationships, including a truly harrowing third marriage to a man who encouraged her addiction to Demerol. Fans of Rachel Cusk and “Borgen,” take note.

‘The Doctors Blackwell: How Two Pioneering Sisters Brought Medicine to Women and Women to Medicine,’ by Janice P. Nimura. (Norton, Jan. 19.)

In 1849, Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman in the United States to earn a medical degree, and encouraged her younger sister Emily to follow suit a few years later. Their interest in the field unnerved many, especially men — one male dean of a medical school wrote, “You cannot expect us to furnish you with a stick to break our heads with” — though neither sister was driven by a strong commitment to the women’s movement or suffrage. Emily’s accomplishments have often been eclipsed by those of her older sister, but Nimura tells both their stories in detail.

Land: How the Hunger for Ownership Shaped the Modern World,’ by Simon Winchester. (Harper/HarperCollins, Jan. 19.)

Using his own land purchase as a jumping-off point, Winchester explores the political, social and emotional meaning humans have attached to property over the centuries. His book takes readers across the world, touching on dispossession, boundary-drawing and humanity’s “frenetic appetite for territory.” (Winchester, whose previous books have taken up the eruption of Krakatoa, the origins of the Oxford English Dictionary, a history of the Atlantic Ocean and other capacious topics, is no stranger to sprawling subject matter.)

‘Let Me Tell You What I Mean,’ by Joan Didion. (Knopf, Jan. 26.)

“Part of the remarkable character of Didion’s work has to do with her refusal to pretend that she doesn’t exist,” Hilton Als writes in the foreword to this collection, composed of essays first published between the late ’60s and 2000. The subjects on offer range from Ernest Hemingway to Nancy Reagan — though Didion’s own subjectivity is never far from the page, as usual.

‘Let the Lord Sort Them: The Rise and Fall of the Death Penalty,’ by Maurice Chammah. (Crown, Jan. 26.)

For many Americans, the death penalty is an abstraction, but Chammah, a reporter at The Marshall Project, zeroes in on the people — lawyers, judges, families — whose lives have been profoundly shaped by the practice. His focus is Texas, which has become an epicenter of capital punishment since the first execution by injection in the United States was carried out there in 1982 — and a state, Chammah argues, whose cultural identity embraces its history of harsh justice.

The Lives of Lucian Freud: Fame, 1968-2011,’ by William Feaver. (Knopf, Jan. 19.)

The second and final volume of this biography traces Freud’s life as his artistic output and notoriety soared. Feaver, a British art critic, draws on his conversations with the famously private painter, interviews with Freud’s family and friends, and more for this examination of a mercurial, manipulative and brilliant artist.

‘No Heaven for Good Boys,’ by Keisha Bush. (Random House, Jan. 26.)

Bush lived in Senegal while working in international development, and draws on those experiences in her first novel. Two cousins work in Dakar as talibé, boys who study the Quran at residential schools and are often forced to beg for money, food and other supplies. There’s plenty of cruelty depicted in these pages — physical and emotional abuse, family separations — but the moments of human kindness and hope keep the story afloat.

The Prophets,’ by Robert Jones Jr. (G.P. Putnam’s Sons, Jan. 5.)

This debut novel centers on a romance between two enslaved men, Samuel and Isaiah, in Civil War-era Mississippi. After another enslaved man discovers their relationship, he attempts to turn the rest of the plantation against them, believing it puts everyone in danger.

Sanctuary: A Memoir,’ by Emily Rapp Black. (Random House, Jan. 19.)

In an earlier book, “The Still Point of the Turning World,” the author wrote about her first child, Ronan, who died of Tay-Sachs disease before he turned 3, and the impossibility of parenting a child without a future. After Ronan’s death, she remarried and had a healthy young daughter. The essays here confront a wrenching question: How can you be the mother of two children, one living and the other dead?

‘Saving Justice,’ by James Comey. (Flatiron, Jan. 12.)

The former F.B.I. director divulged key details about his exchanges with President Trump in a previous memoir, “A Higher Loyalty.” Now, he broadens his focus and registers alarm about the erosion of truth and trust in the United States — and the ramifications for democracy.

A Swim in a Pond in the Rain: In Which Four Russians Give a Master Class on Writing, Reading, and Life,’ by George Saunders. (Random House, Jan. 12.)

Saunders has been a stalwart of the M.F.A. program at Syracuse for years, and here he adapts one of his courses into a book. His essays — paired with fiction from Chekhov, Turgenev, Tolstoy and Gogol — make a case for why literature is essential, even in unsteady times.

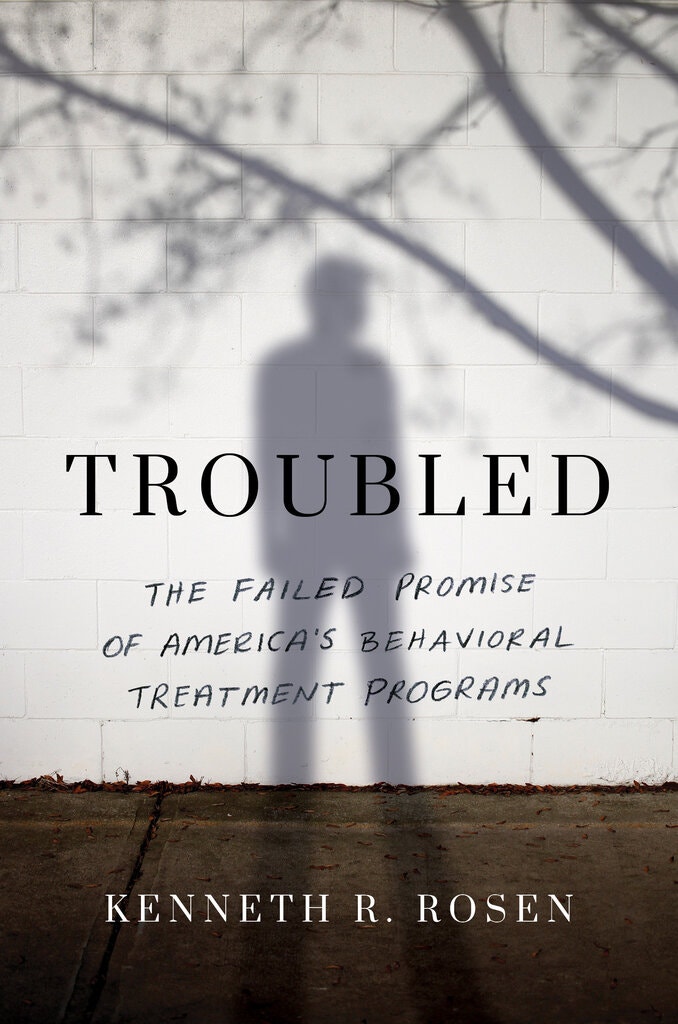

‘Troubled: The Failed Promise of America’s Behavioral Treatment Programs,’ by Kenneth R. Rosen. (Little A, Jan. 12.)

The author, a former New York Times staffer, began collecting material for this book as a teenager, when he was sent to three different therapeutic programs for wayward adolescents. His narrative — anchored by four young adults sent to similar “tough love” environments — shows that many programs inflict lasting damage on the people they claim to help. Ultimately, the book makes a strong case for reforming the practice. “For me, as for many others,” Rosen writes, “the programs were the start of a life spent circulating through countless institutions and lockups.”

The Best Books of the Year 2020

Disclosure: This post is brought to you by aamadmikifaryad.wordpress. We highlight products and services you might find interesting. If you buy them, we get a small share of the revenue from the sale from our commerce partners. We frequently receive products free of charge from manufacturers to test. This does not drive our decision as to whether or not a product is featured or recommended. We welcome your feedback. Email us at futureoftheworldin2050@gmail.com